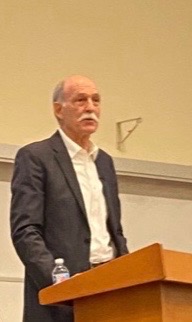

Media Hub: Student Hannah Lang '20 profiles Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Zucchino '73

UNC Hussman students packed the room last month to hear Pulitzer Prize- winning journalist David Zucchino '73 deliver the Nelson Benton lecture and join a panel discussion about his acclaimed book Wilmington's Lie, race relations in America and discuss his long career as a foreign correspondent. UNC Hussman student Hannah Lang '20 interviewed Zucchino throughout his day at the school for the Media Hub and wrote an in-depth, thoughtful profile on his remarkable career. Read Lang's story, below. And don't miss Zucchino's episode of Dean Susan King's Start Here Never Stop podcast.

Three books, one Pulitzer and too many bylines to count: David Zucchino adds another chapter to his half-century in journalism

Story by: Hannah Lang

Photos by: Missy McLamb

He was working in Cairo when he heard the rebels had taken over Benghazi and forced out Gadhafi, practically overnight.

So he packed what he could and dashed for the Libyan border, 400 miles west. No visa, no translator, no guide, no plan.

The rebels at the border let him pass. He hitched a ride on a vegetable truck headed toward the capital, with a driver who spoke little English.

In about a week from now, he’d detail the chaos he was about to see on the streets of Benghazi: Young rebels firing rifles into the air. Teenagers directing traffic. Lawyers, judges, doctors and businessmen taking control of a city and a revolution.

For now though, the vegetable truck is ambling across the desert, ushering him into the belly of a country at war with itself.

****

David Zucchino grew up like any other military kid: moving from base to base, making friends quickly just to lose them in a few years.

It was in high school, when his family settled down in Fayetteville, N.C., that he started to read some of the journalistic greats: John Hersey’s “Hiroshima” and Ernest Hemingway’s war reporting. He thought that might be a nice job to have some day.

“It was always in the back of my mind,” said Zucchino, during an interview on the promotion tour for his latest book, “Wilmington’s Lie.”

“I mean, I wanted to be a journalist and that was the kind of journalist I wanted to be,” Zucchino said. “I wasn’t sure whether I would ever get the opportunity, but it was something that I was very interested in.”

In college at UNC-Chapel Hill, he was sports editor at The Daily Tar Heel. He was a fun-loving and good-natured guy, with a sharp wit he’s kept sharp to this day, said Dan Collins, who worked on the paper’s sports desk at the time.

“At that point, we were taking our jobs seriously. We were not taking life seriously,” Collins said. “He still has that. He’s never lost that.”

When he walked through the doors of The News & Observer looking for a job in 1973, Zucchino was wearing a suit and tie he’d bought at a thrift store, with hair down to his shoulders. He ran into a group of reporters, including Rick Nichols, the paper’s state editor, coming out of the elevator.

Nichols took one look at him.

“Who do you think you are? James Taylor?” Nichols said.

The group laughed. Zucchino blinked, taken aback.

That was his entrance into the news business.

He landed a job as a general assignment reporter and covered anything that needed covering, from state government to the weather.

Writing about the weather was tough. He tried his best to make it interesting. But they print the full weather report in the paper every day, he thought. Who’s going to read another story on the weather?

One day, Nichols had to pull him aside.

“David, you’re writing them too well; you gotta flatten them out a bit,” he said. Did he want to be on the weather beat forever?

****

****

Even in Libya or Lebanon, even in the middle of a war zone, the principles of reporting are the same: Get to the story. Talk to the right people. Ask the right questions. React. Adapt. Write quickly. Meet deadline.

After working almost a decade at newspapers across the country, Zucchino had a pretty good grasp of the basics.

He was working for The Philadelphia Inquirer during the paper’s 15-year Pulitzer streak when the paper’s major competitor, the Philadelphia Bulletin, closed in 1982. That same day, the Inquirer announced the company would open six foreign bureaus.

Zucchino got a call at 2 a.m., asking if he’d be the chief of the bureau in the Middle East. The kind of opportunity he dreamed of while reading “Hiroshima.”

My wife is pregnant, he said. It’s our first child.

Well, don’t worry, they told him. You can wait until the baby is born.

Months later, Zucchino, his wife and his two-month old daughter moved to Beirut.

“It was a very stressful, trying time,” he said.

The Israelis were invading Lebanon.

****

His friends call him fearless, but Zucchino has a different view on how he stumbled into his career as a war correspondent.

“I think what helped is I didn’t even know what I was getting into,” he said. “I didn’t know enough about it… I really had no concept of how dangerous it was or what it was all about.”

But he learned quickly how a situation could turn life-threatening in an instant. It’s something he thinks of constantly, to this day.

“Because you know, you wonder — will this be the time that you don’t come back?” he said. “And that’s pretty much permanent.”

After Lebanon there was Egypt, Bosnia, Iraq, Chechnya, Namibia, Afghanistan and Libya, among other assignments. He wrote stories on apartheid and invasions and war crimes. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998 for his series “Being Black in South Africa.”

“He’s just a really top-notch reporter,” said Bland Simpson, a lifelong friend who works in the music industry and as a creative writing professor at UNC. “He’s fearless in taking the assignments and going where the trouble is.”

Violence, war and political unrest are large, unruly stories. Of all that he’s learned from covering conflict, Zucchino said, the greatest lesson is relatively simple: talk to people.

“I just found that the best stories were about human beings,” Zucchino said. “And if you spend enough time with just day-to-day people who were directly affected, sometimes in horrible ways, by what was going on, you could tell a larger story through their lives.”

People in traumatic situations somehow seem to be more open to talking to a stranger rather than anyone else, he’s observed. But that doesn’t make it easy.

“I am always meeting people on the worst days of their lives,” he said.

****

At 68 years old, Zucchino still spends six months out of the year in Afghanistan, reporting on America’s longest-running war for The New York Times. His wife stays home now, and his three daughters are grown.

In the 30-day intervals he spends at home between trips, he’s managed to put together a 331-page narrative nonfiction book on the 1898 Wilmington massacre, published in January. “Wilmington’s Lie” details the history of the 19th century slaughter of more than 60 black men by armed white supremacists in the racially progressive town of Wilmington, just 99 miles from the town where Zucchino lived as a teenager.

“Nobody ever mentioned it in history class, and no professor ever mentioned it. It wasn’t in history books…” Zucchino said. “But I was just fascinated by the story and the fact that it had never really been told, at least not nationally.”

Zucchino can talk about the book for hours, it seems. In one afternoon at his alma mater in Chapel Hill, he does just that, and answers the same few questions from dozens of students and faculty with unrelenting enthusiasm.

Where’d he get the idea for the book? The town of Wilmington hosted a centennial event in 1998. He read about in the newspaper, and kept the idea in the back of his mind ever since.

How’d he learn so much about the inner lives of people long dead? Diaries and letters, mostly, but also some newspaper editorials and published interviews with survivors of the massacre in the black press.

Has the book been controversial? From what he’s seen, not very — unless someone breaches the topic of reparations, which tends to make the white people in the room very uncomfortable.

He talks with his hands and answers emphatically, without a hint of cynicism.

He’s always been that way, Collins said. He can’t believe Zucchino is still cycling in and out of a war zone when, during his own final years as a sports reporter, Collins could barely drag himself to a Clemson basketball game.

In many ways he’s the same man Collins knew when they were fresh college grads in the early ‘70s, when Zucchino had started for working for The News & Observer. The “good times,” as Collins calls them, when they would catch concerts at Cat’s Cradle and play croquet in thrifted sports jackets.

“But then he had that ability to get up the next morning and go tackle the assignment, and do it better than anybody,” Collins said. “He’d be the best guy there.”

Collins didn’t quite understand it, he said, until they were talking some time ago and Collins brought up a hobby of his, a passion for playing music. It gives him a reason to get up in the morning, he said.

“And David said, ‘Well, that’s me going to Afghanistan,” Collins said. “And it clicked at that moment. I totally understood why he still does it.”

****

In his hotel room in Benghazi, Zucchino wipes the sweat from his brow and sits down at his computer. He begins to type.

In Benghazi, the center of the eastern rebellion that broke free from 41 years of despotic rule a week ago, everyone is in charge — and no one is in charge. But everyone seems to have claimed a piece of the revolution…