Read all about it: Studying women’s contributions to journalism

By Beth Hatcher

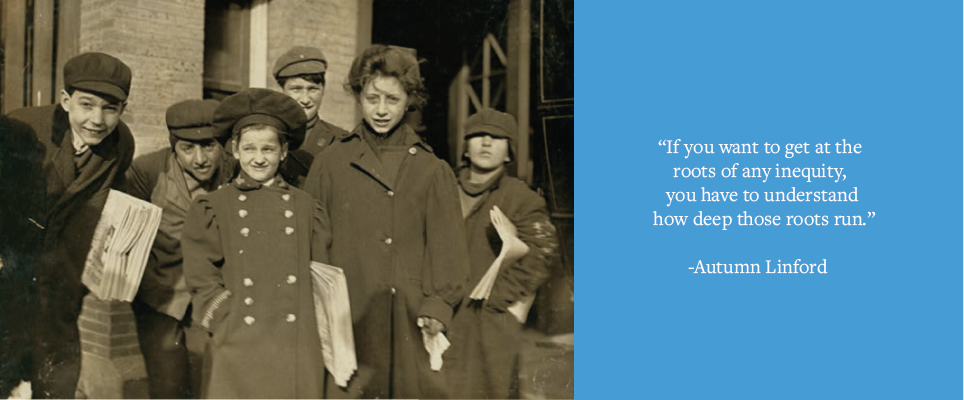

Picture 19th- and 20th-century kids who sold newspapers on the streets in American cities — referred to in slang as newsies.

Now, picture one as female.

That may not come naturally, but according to doctoral student Autumn Linford’s research, female newsies were not so uncommon, though obscured like many of the contributions women have made to journalism history.

“Women have been a part of journalism history as long as there’s been American journalism,” said Linford, pictured at right, who studies journalism history at UNC Hussman and will teach it this fall as an assistant professor at Auburn University in Alabama.

Linford, who has taught at Hussman as an adjunct professor, started her career as a local news reporter in her native Wyoming, at a regional newspaper where she covered everything from sports to local government. A desire to better understand journalism’s impact on society drew her to academia. Society’s impact on journalism, such as a devaluation of women’s professional contributions to the craft, became a focus of her academic work.

“If you want to get at the roots of any inequity, you have to understand how deep those roots run,” Linford said.

In American journalism, some of those roots shoot back to the female newsies, who were little girls trying to do a job, but who were also symbols of a changing public face for women — one with which not everyone was comfortable. In her research, Linford examines how the female newsies’ work coincided with late 19th- and early 20th-century fears that women were stepping out of “proper” feminine roles, often tied to the home.

“Here were these little girls working outside the home — in public, out loud,” Linford said. “They were brash, they were bold. They were not the demure little creatures that they were supposed to be.”

Pictured below: A group of newsies containing female workers. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The little girls were “supposed” to be future wives and mothers only, and society’s rigid expectations of gender roles pushed into newsroom expectations as well.

“Girl newsies have been neglected in the study of our field’s history, despite the fact that they were a vital source of labor at a key period in the development of the commercial press,” said Associate Professor Barbara Friedman, Linford’s adviser. “So Autumn is correcting that oversight by illuminating their experiences using a range of historical artifacts. The period she’s studying was also one of significant social reform, including efforts to limit child labor. While boy newsies were treated as little entrepreneurs, girls were regarded as future wives and mothers, who were harmed by their proximity as street news sellers to vice – alcohol, gambling, prostitution.”

As journalism professionalized in the early 20th century, common social norms meant women in the industry, inside and outside the newsroom, had a harder time succeeding, if they were even given jobs at all, Linford said.

For example, many female journalists were regulated to publications’ “women’s pages,” where they wrote feature-style articles on topics related to domesticity, such as cooking, housekeeping and fashion. Although scholars have illuminated in some of this coverage a feminist response to gender roles, at the time, this “soft news” was generally thought to be less important than news coverage of politics and crime, Friedman said.

But plenty of women broke those rules, women like Nellie Bly, a groundbreaking investigative journalist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whom Linford has also studied in her research.

In a piece published in the academic journal American Journalism, Linford examined historic memorabilia produced by Bly’s fans — everything from hats to lamps to tobacco brands — to learn more about how people viewed women’s changing roles. Bly represented the independent, outspoken “New Woman” ideal emerging in the early 1900s. While many women weren’t yet ready to live like Bly, producing and trading her memorabilia allowed them to contemplate life beyond their traditional roles, Linford concluded.

“One of Autumn’s first studies in the doctoral program used historical labor data and trade publications to understand women’s early entrance to news work, and how women were regarded in those spaces,” Friedman said. “I love Autumn’s embrace of the ‘read everything’ ethos of history, and likewise, her enthusiasm for archival work. Her ability to think historically is one of the many strengths she gifts to our field.”

Linford’s research has allowed her to contemplate inequities she has experienced in the 21st century as a female journalist — such as work conditions that still don’t support mothers and the fact that she’s had only one female editor in her career.

Linford credits her work as a journalist — learning how to dig for information, find interesting sources and write concisely — with helping her academic success.

Next, she’ll help others succeed in her roles as researcher and teacher, roles she sees as critical at a time as the journalism industry changes rapidly.

As digital platforms and new funding models restructure the future of news, understanding its history — of all its players — has never been more important, Linford said. “And I enjoy telling the story of the storytellers.”