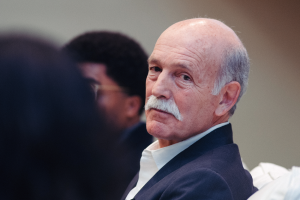

Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner David Zucchino ’73 and Dean Susan King have wide-reaching conversation about Afghanistan

by Barbara Wiedemann

More than 230 UNC Hussman community members from around the country logged into Zoom at 5 p.m. on Wednesday, September 29, under the UNC Hussman Webinar Series banner for a unique opportunity to hear from one of the country’s most widely respected foreign correspondents on his 20-year-long view of Afghanistan. Danita Morgan ’81, associate dean for development and alumni affairs at the school, welcomed the audience to what proved to be a wide-reaching virtual conversation between UNC Hussman alumnus David Zucchino ’73 and Dean Susan King about the context behind Afghanistan in the news.

Zucchino is a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent — for feature writing (1989) and general nonfiction (2021) — who has reported from more than three dozen countries.

After graduating from what was then the “J-school” under Dean Richard Cole in 1973, Zucchino reported for The News & Observer (1973–78), The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Los Angeles Times before becoming a contributing writer for The New York Times. He has covered Afghanistan for two decades.

Talking with alumni, students, faculty and staff from his home in Durham, North Carolina, Zucchino deftly kept pace with a slew of insightful questions set to him at a rapid clip by Dean King, who was logged in from Carroll Hall.

The journalist and author explained that he still held one of the last visas granted by the Afghan government — “good through November,” he noted, and was trying to figure out how to get back. The nation is now under Taliban rule for the first time since a U.S.-led invasion toppled the regime in response to the terrorist attack on the U.S. on September 11, 2001. Over the course of an hour, he gave a concise history of U.S. involvement in Afghanistan since 2001 and put the landlocked nation neighbored by Pakistan to the east and south and Iran to the west in geographic and cultural context for the audience while answering many questions about the recent regime change.

“Women have been erased from public life”

“Things are pretty awful,” Zucchino said when asked to describe the state of that country today. “Women have been pretty much erased from public life. That didn’t take long,” reporting that since the takeover, women are no longer visibly working in government, parliament, as judges, lawyers, teacher or in the press.

“One of the real achievements of the 20 years that the United States spent in Afghanistan was a vibrant and free and independent press, and we spent a lot of money to create this,” Zucchino said of the place and the people he’s been reporting on since the U.S invaded. “The Taliban has come in and crushed it.”

Initial reassurances that the Taliban would be responsible stewards of Afghanistan, Zucchino noted, were most likely communicated by a diplomatic wing that has since been outflanked by more hard-line military commanders.

Asked to talk about what Afghani women are telling him about the new regime, Zucchino referred to his recent reporting with Victor Blue, “A Harsh New Reality for Afghan Women and Girls in Taliban-Run Schools.”

“They are absolutely depressed. Terrified. It’s hard to get across how shocking and sudden this was. One minute they are in school, at university, teaching. The next minute, it’s all gone.” He added, “I think many are still in shock. The other thing that strikes me is they don’t know what is going to happen.”

The journalist wondered if what he described as a very computer-savvy community of young Afghani women who have grown up active on social media might have to educate themselves online, providing the Taliban doesn’t shut off access to the internet.

Military “might have had a pretty good idea that things were really falling apart quickly” if they’d read the newspapers

How did the Afghani ruling government’s collapse and Taliban takeover happen so quickly?

Zucchino’s report on August 15 of this year detailed the chaotic scene.

In his talk, he pointed to evidence he’d gathered for a May 2021 story (“A Wave of Afghan Surrenders to the Taliban Pick Up Speed”) about how the Taliban was rapidly negotiating surrenders with desperate police and army officials in the provinces who had gone without pay for months and were not receiving food, water or ammunition.

The message, he said, was, “You’re surrounded. You can't get resupplied, your government doesn't care about you. They've sold you out. If you will surrender and hand over all your weapons and equipment, we will let you live, and in fact will give you some money to give you a bus ticket home.”

He reminded the audience that Afghani forces lost 60,000 men over the course of the two-decade-long invasion.

Zucchino said that he and others reported over the spring and summer months that the Taliban had taken almost complete control of all major highways around Afghanistan and in essence, could control the country by blocking supplies traveling to garrisons and bases. A fall of the regime was predictable, he said, but “I was thinking fall or winter. Nobody thought it would happen by August.”

Answering a question about how intelligence missed the immediacy of the Afghani regime’s collapse, Zucchino said that in his opinion, the U.S. was fighting not a 20-year war but 20 one-year wars in Afghanistan, with troops on rotations of 8 to 12 months and commanders pressed to show progress in that timespan. He noted how difficult it was — even as a long-time reporter on the ground — to follow the complexity of Afghani religious, ethnic and tribal divides and the fluid allegiances of those parties. But here he also referred back to reports over the summer of surrenders, corruption and falling bases and said bluntly, “if the military had just read the newspapers, they might have had a pretty good idea that things were really falling apart quickly.”

“Please help me. I’ve got to get out.”

Zucchino answered a question about how the Times worked to get staffers and their families out of Afghanistan in August.

“This was a very traumatic and harrowing time. I’m here safely in the United States, and it was traumatic for me. I can only imagine what our people were going through,” he said as he described the chaotic exit, with families attacked and beaten on their way to the airport in Kabul, where they waited without food and water for a flight out while bureaucratic procedural nightmares ensued.

He detailed how Mexico City eventually accepted the refugees. Since then, they have received humanitarian parole from the U.S. State Department, he said, adding, “They're in Houston now with a resettlement agency. They're getting apartments, getting set up and beginning the process for asylum.”

The reporter continues to get calls, emails and texts from Afghani colleagues and former interview subjects, begging him for help in getting out of Afghanistan.

“I just got calls this afternoon from people,” he said, visibly shaken. “They say ‘Please help me. I’ve got to get out. I’m hiding and the Taliban is threatening me.’”

Asked what an individual could do in the face of so much need, Zucchino said simply, “Humanitarian assistance.”

He urged those wanting to make a difference to help groups like the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the U.S. Agency for International Development and others who will have to work to find ways to ensure that their aid goes to the people rather than the Taliban.

Thank you

The talk closed with a thank you from alumna Angie Sloan ’03, who wrote that she’d been honored to meet Zucchino when she interviewed him for a journalism school story on embedded journalists nearly 20 years ago and was grateful to be hearing from him now.

“It’s nice to have a fan, thank you,” Zucchino quipped.

For more from David Zucchino on Afghanistan, including why he prefers to travel in a beat-up old white Toyota when he is in-country, please watch for a video of the webinar to be posted here later this week.

Click here for our story on David Zucchino’s February 2020 talk about his Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Wilmington’s Lie.”